Special mentions (4.5 stars):

Monday, December 31, 2018

Thursday, December 20, 2018

The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia by Ursula K. Le Guin (3 stars)

The Dispossessed is very philosophical sci-fi. Effectively the aliens are just there to explore a large thought experiment about an anarchist utopia, just as left hand of darkness is an expose by contrast of the effect of gender differences we have created in our society.

There's a study guide at the back of the book, which I wish I'd read with each chapter, it would have given me a deeper understanding. One thing it points out is the historical context: following the dystopias popular in the mid 1900s, this novel was one of a few new utopias written in the mid 70s that attempted to be more realistic - not implausibly perfect and unattainable.

So in this novel Le Guin presents Anarres, where an anarchist society has succeeded in a very harsh environment, but is far from perfect. Rather than a government, policy, and military controlling the populace, the job of enforcing social norms and enacting any punishment for deviance from those norms is essentially left to your neighbours and colleagues. The stick they wield is removal of social approval and casting out of those who don't conform.

As well as exploring how an anarchist society could work, Le Guin continues a strong sexual equality discourse that was familiar from left hand. Shevek is shocked at the reactions he gets from people on Urras when discussing how men and women were effectively equal on Anarres:

There's a study guide at the back of the book, which I wish I'd read with each chapter, it would have given me a deeper understanding. One thing it points out is the historical context: following the dystopias popular in the mid 1900s, this novel was one of a few new utopias written in the mid 70s that attempted to be more realistic - not implausibly perfect and unattainable.

So in this novel Le Guin presents Anarres, where an anarchist society has succeeded in a very harsh environment, but is far from perfect. Rather than a government, policy, and military controlling the populace, the job of enforcing social norms and enacting any punishment for deviance from those norms is essentially left to your neighbours and colleagues. The stick they wield is removal of social approval and casting out of those who don't conform.

As well as exploring how an anarchist society could work, Le Guin continues a strong sexual equality discourse that was familiar from left hand. Shevek is shocked at the reactions he gets from people on Urras when discussing how men and women were effectively equal on Anarres:

“Is there really no distinction between men’s work and women’s work?” “Well, no, it seems a very mechanical basis for the division of labor, doesn’t it? A person chooses work according to interest, talent, strength—what has the sex to do with that?” “Men are physically stronger,” the doctor asserted with professional finality. “Yes, often, and larger, but what does that matter when we have machines?

Kimoe stared at him, shocked out of politeness. “But the loss of—of everything feminine—of delicacy—and the loss of masculine self-respect— You can’t pretend, surely, in your work, that women are your equals? In physics, in mathematics, in the intellect? You can’t pretend to lower yourself constantly to their level?”And there's a fairly profound portrayal of how messed up our way of speaking about sex is:

The language Shevek spoke, the only one he knew, lacked any proprietary idioms for the sexual act. In Pravic it made no sense for a man to say that he had “had” a woman. The word which came closest in meaning to “fuck,” and had a similar secondary usage as a curse, was specific: it meant rape. The usual verb, taking only a plural subject, can be translated only by a neutral word like copulate. It meant something two people did, not something one person did, or had.Shevek can't comprehend why the women of Urras put up with this situation:

“It seems that everything your society does is done by men. The industry, arts, management, government, decisions. And all your life you bear your father’s name and the husband’s name. The men go to school and you don’t go to school; they are all the teachers, and judges, and police, and government, aren’t they? Why do you let them control everything? Why don’t you do what you like?”It's all very thoughtful, the subject is important, and the premise is well constructed. I can see why it won tons of awards. But honestly I just didn't enjoy reading it so I can't give it a high rating. Too much sitting around philosophizing and reflecting on events, and not enough first-person experiencing of events. There's plenty of passages that feel like reading a philosophy textbook that I just found boring:

3 stars.Suffering is dysfunctional, except as a bodily warning against danger. Psychologically and socially it’s merely destructive.” “What motivated Odo but an exceptional sensitivity to suffering—her own and others’?” Bedap retorted. “But the whole principle of mutual aid is designed to prevent suffering!”

Sunday, December 2, 2018

Rendezvous with Rama by Arthur C. Clarke (5 stars)

I loved this one, originally published in 1972 it has held up well, sans some uncomfortable sexism. It won all the awards (Hugo, Nebula, and others). It's a fascinating exploration of an unknown alien object.

There's absolutely no character development. It could almost be a scientific journal article, but it's actually a really interesting discovery and exploration story. One of my favourite parts was the attention to detail about travel through the artifact, including mind games played on the explorers by low gravity in an enormous indoor space:

There's absolutely no character development. It could almost be a scientific journal article, but it's actually a really interesting discovery and exploration story. One of my favourite parts was the attention to detail about travel through the artifact, including mind games played on the explorers by low gravity in an enormous indoor space:

Too much thinking along these lines evoked yet a third image of Rama, which he was anxious to avoid at all costs. This was the viewpoint that regarded it once again as a vertical cylinder, or well—but now he was at the top, not the bottom, like a fly crawling upside down on a domed ceiling, with a fifty-kilometer drop immediately below. Every time he found this image creeping up on him, he needed all his will power not to cling to the ladder in mindless panic.It's well written, but fairly cold and impersonal, with some rare more poetic moments like this:

Rama is a cosmic egg, being warmed by the fires of the Sun. It may hatch at any moment.” The Chairman of the committee looked at the Ambassador from Mercury in frank astonishment.Quibbles:

- It seems really unlikely to me that aliens would have similar body geometry to humans, but the explorers don't seem to find this remarkable at all. I was waiting to find out that it's actually a human artifact created by time-travelling humans...

- Space travel is more advanced than present day, but I found the amount of extra equipment lying around unused on a spaceship that wasn't built as an exploration vessel stupidly implausible. There's crates and crates of equipment brought into Rama, spare 20kW electric motors, and even a recreational plane-bike???

And on the sexism, it was sad to see how many times "men" was written in sentences like these, but also not surprising for the 70's:

...at least for men who were trained to face the realities of space. Perhaps no one who had never left Earth, and had never seen the stars all around him, could endure these vistas. But if any men could accept them, Norton told himself with grim determination, it would be the captain and crew of the Endeavour. He looked at his chronometer.

The reviews of the sequels are terrible, so I'll probably stop at this one.

5 stars.

Sunday, November 25, 2018

The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August by Claire North (5 stars)

Great read, I breezed through it over a couple of days. Time travel is one of my favourite subjects, and I liked the premise of being trapped constantly re-living the same life in the same body, but with memories carrying over after your death. Like Groundhog day, but for your whole life instead of one day.

What would you do if you had essentially infinite lives? What would matter to you? How would you value the lives of others who aren't like you (referred to as linear)?

North gives Harry plenty of opportunity to explore those questions. He discovers the "Cronus Club": an organization of kalachakras like himself that assists those who have been reborn as children with escaping the tedium of going through yet another childhood, and establishing some income and housing stability. A common view of those in the Chronus Club is that "complexity should be your excuse for inaction": the reasoning being that if you were to kill Hitler for example, how do you know that an even more effective leader with the same views wouldn't take his place, and possibly win World War Two? Through trying to influence the world in many ways the consensus of the Chronus Club is that the large historical events are largely fixed and mostly immune to change.

Given that WWII will always happen no matter what you do, how would you choose to live your life? Some escape to calmer countries during the war, some fully participate and revel in the unpredictability of war because it delivers new experiences each time.

Ironically, to give purpose to the lives of the Chronus Club members, some sort of mutual objective is desirable, and one materializes in the form of Vincent, our antagonist. Vincent's only real crime is chasing a macguffin, in this case a quantum mirror which will help him understand time and matter on a much deeper level. He pursues it with ruthless efficiency, killing those who get in his way, and with no care for how much he may be changing the course of history in the process. He perfects methods to create advanced technology faster than it was ever supposed to happen - delivering gift-wrapped inventions to the best scientists of the time. I've often wondered about this subject myself: given modern education, and the ability to time travel, how effective could a single person be at accelerating technological advancement? Vincent is certainly helped by having a photographic memory.

I loved the idea of handing messages forward and backwards through time by passing them young to old, old to young through the Chronus club. The implication received through these messages from the future is that technological advancement precipitates environmental collapse, and bringing forward the pace of that change, also brings forward the end of the world.

There's some logic holes that aren't really explained in the story: say Harry and Vincent are separated by 10 years at birth, but Harry dies at 20 and Vincent lives for another 50 years. If Harry is reborn and then Vincent is reborn 10 years later with all of his extra 50 years of memories, was Harry waiting in limbo for 50 years? Multiply that problem by thousands of kalachakras.

Spoilers.

The ending seems a little too easy. Vincent just gives up his point of origin for no good reason. I didn't buy Harry's strategy of talking to him about his own childhood in an effort to get Vincent to divulge his, Vincent guarded that secret as his most prized possession for hundreds of years. Also I didn't buy that Harry wouldn't slip up over several decades of working closely with Vincent. It would have happened somehow, some bit of knowledge would have peeked through. Harry's very long-game strategy just wouldn't have worked. I especially don't think he could have maintained composure through the Jenny incident.

Overall though, spectacular read.

5 stars.

What would you do if you had essentially infinite lives? What would matter to you? How would you value the lives of others who aren't like you (referred to as linear)?

North gives Harry plenty of opportunity to explore those questions. He discovers the "Cronus Club": an organization of kalachakras like himself that assists those who have been reborn as children with escaping the tedium of going through yet another childhood, and establishing some income and housing stability. A common view of those in the Chronus Club is that "complexity should be your excuse for inaction": the reasoning being that if you were to kill Hitler for example, how do you know that an even more effective leader with the same views wouldn't take his place, and possibly win World War Two? Through trying to influence the world in many ways the consensus of the Chronus Club is that the large historical events are largely fixed and mostly immune to change.

Given that WWII will always happen no matter what you do, how would you choose to live your life? Some escape to calmer countries during the war, some fully participate and revel in the unpredictability of war because it delivers new experiences each time.

Ironically, to give purpose to the lives of the Chronus Club members, some sort of mutual objective is desirable, and one materializes in the form of Vincent, our antagonist. Vincent's only real crime is chasing a macguffin, in this case a quantum mirror which will help him understand time and matter on a much deeper level. He pursues it with ruthless efficiency, killing those who get in his way, and with no care for how much he may be changing the course of history in the process. He perfects methods to create advanced technology faster than it was ever supposed to happen - delivering gift-wrapped inventions to the best scientists of the time. I've often wondered about this subject myself: given modern education, and the ability to time travel, how effective could a single person be at accelerating technological advancement? Vincent is certainly helped by having a photographic memory.

I loved the idea of handing messages forward and backwards through time by passing them young to old, old to young through the Chronus club. The implication received through these messages from the future is that technological advancement precipitates environmental collapse, and bringing forward the pace of that change, also brings forward the end of the world.

There's some logic holes that aren't really explained in the story: say Harry and Vincent are separated by 10 years at birth, but Harry dies at 20 and Vincent lives for another 50 years. If Harry is reborn and then Vincent is reborn 10 years later with all of his extra 50 years of memories, was Harry waiting in limbo for 50 years? Multiply that problem by thousands of kalachakras.

Spoilers.

The ending seems a little too easy. Vincent just gives up his point of origin for no good reason. I didn't buy Harry's strategy of talking to him about his own childhood in an effort to get Vincent to divulge his, Vincent guarded that secret as his most prized possession for hundreds of years. Also I didn't buy that Harry wouldn't slip up over several decades of working closely with Vincent. It would have happened somehow, some bit of knowledge would have peeked through. Harry's very long-game strategy just wouldn't have worked. I especially don't think he could have maintained composure through the Jenny incident.

Overall though, spectacular read.

5 stars.

Friday, November 23, 2018

Who fears death by Nnedi Okorafor (3 stars)

Coming off the Binti series underwhelmed I wasn't sure I should dive into another Okorafor book, but I was intrigued because HBO had bought the options on it as a series with George RR Martin as the executive producer. Minor spoilers ahead

Okorafor sets out to tackle some heavy subjects: rape, female circumcision, colourism, racism, sexism, and ethnic cleansing. She succeeds in showing us what it would be like to be pressured by society and tradition into circumcision, what it would be like to be the child of rape where your very skin colour screams to everyone that you were a child of rape. Just your skin colour makes you an outcast, constantly reviled and hated. Sadly, this is based on true events in Sudan:

This is all heavy, heavy stuff, but it is dealt with in well crafted storytelling...for a while. But soon I found the story stalling. I expected to get a sorcery training montage, but didn't. All of Onyesonwu's 'training' was mostly just starving her, throwing her into a deadly situation and seeing if she could figure out what to do instinctively. Somehow this makes her incredibly powerful, by her own account. That's unconventional, but OK.

I also expected to get more deep character development, but didn't. Even Mwita, the second most important character, is basically just a skin colour (also Ewu) who is in love with Onyesonwu. The girls who go through the circumcision with Onyesonwu become her friends, but are almost entirely defined by wanting the circumcisions undone so they can have sex. We know very little else about them except Luyu is probably the prettiest.

Sex is had and talked about constantly as the group of friends start their voyage, but there aren't actual sex scenes, just lots of talk about hearing people have sex in other tents. Its repetitive and boring.

After reading a number of Okorafor books, I think the lack of character development outside the main character is a pattern. There's no secondary point of view, and everyone else is a cutout. The villain nemesis in this story is crudely drawn as a pure evil rapist sorcerer:

The ending was essentially what I expected, although with a decent twist, i.e. Onyesonwu doesn't know what to do, acts instinctively using her enormous powers, and saves the day.

It may be possible to make a decent TV series out of this, although it will definitely be hard to watch due to all the violence. It is largely experienced second-hand in the book, but I assume you'll get that first hand on the screen.

The strength of the novel is the real-world hardships and Onyesonwu coming of age in a world where she is beset by multiple -isms. The fantasy/magic side of it is very weak.

3 stars.

Okorafor sets out to tackle some heavy subjects: rape, female circumcision, colourism, racism, sexism, and ethnic cleansing. She succeeds in showing us what it would be like to be pressured by society and tradition into circumcision, what it would be like to be the child of rape where your very skin colour screams to everyone that you were a child of rape. Just your skin colour makes you an outcast, constantly reviled and hated. Sadly, this is based on true events in Sudan:

The female circumcision where they mutilate young healthy girls is also barbaric:The Nuru men, and their women, had done what they did for more than torture and shame. They wanted to create Ewu children. Such children are not children of the forbidden love between a Nuru and an Okeke, nor are they Noahs, Okekes born without color. The Ewu are children of violence.

Onyesonwu obviously has magical talents, but sexism prevents her from receiving any proper tuition despite her life being under threat in the magical world "the wilderness" from her biological father, rapist, and powerful sorcerer.“The scalpel that they use is treated by Aro. There’s juju on it that makes it so that a woman feels pain whenever she is too aroused . . . until she’s married.”

This is all heavy, heavy stuff, but it is dealt with in well crafted storytelling...for a while. But soon I found the story stalling. I expected to get a sorcery training montage, but didn't. All of Onyesonwu's 'training' was mostly just starving her, throwing her into a deadly situation and seeing if she could figure out what to do instinctively. Somehow this makes her incredibly powerful, by her own account. That's unconventional, but OK.

I also expected to get more deep character development, but didn't. Even Mwita, the second most important character, is basically just a skin colour (also Ewu) who is in love with Onyesonwu. The girls who go through the circumcision with Onyesonwu become her friends, but are almost entirely defined by wanting the circumcisions undone so they can have sex. We know very little else about them except Luyu is probably the prettiest.

Sex is had and talked about constantly as the group of friends start their voyage, but there aren't actual sex scenes, just lots of talk about hearing people have sex in other tents. Its repetitive and boring.

After reading a number of Okorafor books, I think the lack of character development outside the main character is a pattern. There's no secondary point of view, and everyone else is a cutout. The villain nemesis in this story is crudely drawn as a pure evil rapist sorcerer:

Real villains are much more complex. What was his motivation for these terrible acts? We don't know.“Some people are just born evil,”

The ending was essentially what I expected, although with a decent twist, i.e. Onyesonwu doesn't know what to do, acts instinctively using her enormous powers, and saves the day.

It may be possible to make a decent TV series out of this, although it will definitely be hard to watch due to all the violence. It is largely experienced second-hand in the book, but I assume you'll get that first hand on the screen.

The strength of the novel is the real-world hardships and Onyesonwu coming of age in a world where she is beset by multiple -isms. The fantasy/magic side of it is very weak.

3 stars.

Thursday, October 4, 2018

Binti: The Night Masquerade by Nnedi Okorafor (2 stars)

The first in this series showed a lot of promise, but the rest failed to hold my interest, and this was the weakest of the trilogy. Despite this being a short novel I found myself struggling to finish it. Spoilers ahead.

In a really obvious plot quirk, Binti doesn't investigate the fire in the root where supposedly her entire family perished. Wouldn't you want to know? What if they were still alive? Spoiler: they are still alive, she finds out later. This was very awkward plot construction.

It takes a long time to walk anywhere. I don't understand this world where the technology exists for spaceships, but people don't even have bikes? Pedicabs? Scooters? Motorbikes? Cars?

Just like in the first novel, Binti just has to ask and interplanetary wars stop. These two races have a long and bloody history, and just started a new war, but Binti says:

When she dies it's super obvious she is going to be resurrected by some deus ex machina bullshit at Saturn. My only surprise was that it wasn't the favourite deus ex otjize (I was so sick of hearing about otjize) which has no end of magical properties. Instead it turned out to be even more lame, it's the "microbes", duuuude:

And then we find out that this whole thing with the edan was just the most complicated way possible to solicit a Yelp review for a university.

and then we find out Binti has essentially enslaved New Fish:

In this series Okorafor explored some powerful topics of racism and coming of age for a young woman. But it ultimately fell flat for me on weak characters other than Binti and unbelievable hairpin plot turns.

2 stars.

In a really obvious plot quirk, Binti doesn't investigate the fire in the root where supposedly her entire family perished. Wouldn't you want to know? What if they were still alive? Spoiler: they are still alive, she finds out later. This was very awkward plot construction.

It takes a long time to walk anywhere. I don't understand this world where the technology exists for spaceships, but people don't even have bikes? Pedicabs? Scooters? Motorbikes? Cars?

Just like in the first novel, Binti just has to ask and interplanetary wars stop. These two races have a long and bloody history, and just started a new war, but Binti says:

The war between Khoush and Meduse endsshoots out some lightning, and everyone agrees to stop fighting. Right.

When she dies it's super obvious she is going to be resurrected by some deus ex machina bullshit at Saturn. My only surprise was that it wasn't the favourite deus ex otjize (I was so sick of hearing about otjize) which has no end of magical properties. Instead it turned out to be even more lame, it's the "microbes", duuuude:

"When your body was placed in my chamber, my microbes went to work. You are probably more microbes than human now."It's super lazy. The author might as well have said "bacteria", "space dust" or "icing sugar" for all the sense that makes.

I frowned. "What does that mean? I look and feel like myself. I remember who I am. I was dead, right?"

And then we find out that this whole thing with the edan was just the most complicated way possible to solicit a Yelp review for a university.

"So you've known I would eventually be...what I now am, so you sent for me?"Meanwhile, turns out the war is back on, but now Binti is safely ensconced at the University and the president tells her:

"Yes. We are many things. What is your opinion of the university?"

But until then, don’t worry too much. This fight is old and if the Enyi Zinariya are going to help the Himba, then at least your families will be safe. With you gone, the Khoush will not bother with the Himba, I don’t think.”So, essentially: "don't worry that you triggered a war, this has been going on for ages. I mean wars are pretty sensible and innocent people don't tend to get hurt, so I'm sure your family still on the planet will be fine."

and then we find out Binti has essentially enslaved New Fish:

“About five miles on land and she can fly about seven miles up,” she said. “That’s not so bad, is it?” I smiled and said, “No. Thank the Seven.” “But unless she follows, no more taking university and solar shuttles, okay? New Fish can take you.”So, because she saved your life, New Fish now needs to follow around wherever Binti wants to go, never moving away more than a few miles. And the president has no problem committing New Fish to shuttling Binti around whenever she want for the rest of Binti's life. And it doesn't even seem to occur to Binti that she just made New Fish her slave. WTF?

In this series Okorafor explored some powerful topics of racism and coming of age for a young woman. But it ultimately fell flat for me on weak characters other than Binti and unbelievable hairpin plot turns.

2 stars.

Monday, September 10, 2018

Binti: Home (2.5 stars)

Less interesting than the first, with no interesting characters except for Binti. I think the novella format is very constraining. Okorafor is doing a large amount of world building, but doesn't have time to bring in any other realistic characters.

Binti is going through a coming-of-age, after her trip off-planet has changed her physically and spiritually. She finds the world she left is no longer the one she knew, and confronts prejudice in the form of traditional role beliefs held by her family and friends that don't allow for wild off-planet alien adventures.

She also confronts her own latent racism about the Desert People, and there's a moment of afrofuturism similar to Black Panther when their technology prowess is revealed.

2.5 stars

Binti is going through a coming-of-age, after her trip off-planet has changed her physically and spiritually. She finds the world she left is no longer the one she knew, and confronts prejudice in the form of traditional role beliefs held by her family and friends that don't allow for wild off-planet alien adventures.

She also confronts her own latent racism about the Desert People, and there's a moment of afrofuturism similar to Black Panther when their technology prowess is revealed.

Fairly disappointing follow-up to the first novel.I felt a sting of shame as I realized why I hadn’t understood something so obvious. My own prejudice.

2.5 stars

Sunday, September 9, 2018

Binti by Nnedi Okorafor (3.5 stars)

Since the other ones were so good I started on a full Okorafor binge. So the Binti series was next. The first is super short (98 pages) and won the Hugo and Nebula for best novella.

The strength of the novel is Binti and the desert culture she comes from. Especially her struggles with systemic racism on many fronts. It's written very simply, which I found a little annoying, but since it is YA I can't actually criticize for that.

Plot wise there's a literal deus ex machina, which was a bit of a cop out, and I also just didn't buy how easily this genocidal spaceship of jellyfish could be diverted from their original mission. Even more implausibly a young girl single-handedly negotiated a multi-planetary peace deal that ended happily ever after: real peace deals end with everyone at least slightly unhappy.

3.5 stars

The strength of the novel is Binti and the desert culture she comes from. Especially her struggles with systemic racism on many fronts. It's written very simply, which I found a little annoying, but since it is YA I can't actually criticize for that.

Plot wise there's a literal deus ex machina, which was a bit of a cop out, and I also just didn't buy how easily this genocidal spaceship of jellyfish could be diverted from their original mission. Even more implausibly a young girl single-handedly negotiated a multi-planetary peace deal that ended happily ever after: real peace deals end with everyone at least slightly unhappy.

3.5 stars

Friday, September 7, 2018

Akata Warrior by Nnedi Okorafor (5 stars)

I didn't realise this one took 6 years to follow the original Akata Witch. I'm glad I got to read them back to back, but now I'm worried about how long it will take for the next one :(

Okorafor continues to impress in this YA series. In this novel we learn some more about Nigerian culture, including the very real and dangerous secret societies/gangs ruling Nigerian universities. This sounds fairly ridiculous to the western ear, universities are about the furthest thing from gang territory possible, but I looked it up, it's no joke. I feel like I've been missing this from so much other fantasy: you mean I can get a kick out of exploring this new amazing world, but also learn something about other cultures at the same time?

Sunny struggles with loyalty to her family, and pushes the limits of how she can use magic against/for Lambs. There's also an extended dreamlike episodic sequence as our merry band of Leopard kids heads on a dangerous quest. I loved this bit: giant spiders, and grashcoatah who is now one of my favourite fantasy characters of all time. I loved the description of him/it getting birthed by Udide in a cave full of spiders:

Favourite quote:

Okorafor continues to impress in this YA series. In this novel we learn some more about Nigerian culture, including the very real and dangerous secret societies/gangs ruling Nigerian universities. This sounds fairly ridiculous to the western ear, universities are about the furthest thing from gang territory possible, but I looked it up, it's no joke. I feel like I've been missing this from so much other fantasy: you mean I can get a kick out of exploring this new amazing world, but also learn something about other cultures at the same time?

Sunny struggles with loyalty to her family, and pushes the limits of how she can use magic against/for Lambs. There's also an extended dreamlike episodic sequence as our merry band of Leopard kids heads on a dangerous quest. I loved this bit: giant spiders, and grashcoatah who is now one of my favourite fantasy characters of all time. I loved the description of him/it getting birthed by Udide in a cave full of spiders:

The mass was undulating. The blue marble light only lit part of it. There was something inside. Unt, unt, unt, the thing inside grunted. It sounded like a giant pig.Like the first book, the climax seems over too quickly and implausibly. I loved that she poked at bit of fun at the obvious Harry Potter similarities:

“You mean being doubled?” Sunny said. “Sheesh, it’s not like Voldemort’s name, you can say it aloud.”Random questions/comments:

- What's up with Guinness? Is that seriously a popular drink in Nigeria? It's mentioned a lot in the book.

- Sunny, it's time to eat something other than fried plantain, you need some vegetables.

- I had no idea teeth sucking was a thing, I had to go look it up.

Favourite quote:

When Lambs don’t understand something or they forget the real story of things, they replace it with fear.5 stars.

Tuesday, August 14, 2018

Akata Witch by Nnedi Okorafor (4.5 stars)

After never having read a Nigerian author before, I've read two back to back recently. That's great. This series also promises to be a blockbuster. It's Nigerian harry potter YA fiction.

Sunny is Harry. The outsider brought into a magical world, for which she has a natural talent, but has a lot of catching up to do with children who have already been studying magic for years.

Lambs are Muggles.

Leopard Knocks is Diagon Alley, and the introduction to magic happens in a very similar way through an unusual entrance ritual then a tour of magical shops.

Orlu is Hermione: technically brilliant at magic, but a little cautious, and always getting Sunny out of a tricky spot.

Witch school is in a small group or 1:1 led by experienced teachers, rather than institutional-style Hogwarts.

Ekwensu is Voldemort.

Sunny is Harry. The outsider brought into a magical world, for which she has a natural talent, but has a lot of catching up to do with children who have already been studying magic for years.

Lambs are Muggles.

Leopard Knocks is Diagon Alley, and the introduction to magic happens in a very similar way through an unusual entrance ritual then a tour of magical shops.

Orlu is Hermione: technically brilliant at magic, but a little cautious, and always getting Sunny out of a tricky spot.

Witch school is in a small group or 1:1 led by experienced teachers, rather than institutional-style Hogwarts.

Ekwensu is Voldemort.

So, assuming you're OK with it following a very established pattern, it's great. The magic feels very different from Harry potter, drawing heavily on Nigerian mythology. The real strength of the novel is those Nigerian experiences: foods, scenery, home life, mythology. All of these feel very foreign to a western reader, and it's a refreshing experience.

I also really like the currency of the Leopard world - you can only gain it by learning something! And it drops from the sky instantly when you do, in proportion to the difficulty of the concept/skill mastered. Not only is that an amazing thought experiment for what capitalism would look like under such conditions, it's a clever literary device to signal to the reader "that was a big deal".

The weaknesses are (some spoiler-ish talk):

Sunny is a Mary-Sue: she's not only intuitively great at all sorts of magic, she's a pro soccer player. Although I have to cut it some slack on that point, as her soccer prowess was used to challenge the gender stereotyping and sexism in Nigerian society.

This super-powerful community of Leopard people somehow needs a group of inexperienced kids to find a serial killer and stop him from bringing the most powerful masquerade into the regular world.

The good guys win at the climax far too easily and everything is fine. Magic is a very tempting deus ex machina for the author here.

4.5 stars

Saturday, August 11, 2018

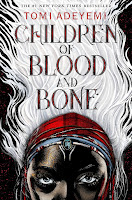

Children of Blood and Bone by Tomi Adeyemi (4.5 stars)

This is a spectacular Young Adult fantasy debut novel by Tomi Adeyemi, a Nigerian-American. All the characters in the story are black, but the ruling class k'osidan is a lighter shade, and has brutally suppressed darker skinned maji citizens, especially the once-powerful magicians among them.

The author draws heavily on the Black Lives Matter movement, and there are strong themes of colorism, and racism throughout. Adeyemi says her aim was to teach via fantasy, in a non-preachy way:

Zelie is a realist about her world, the parallel in our modern world is drivingwhileblack, movingwhileblack etc:

There's some annoyances, I'm unsure whether to chalk this up to simplification to keep it YA approachable, but these rubbed me the wrong way:

The author draws heavily on the Black Lives Matter movement, and there are strong themes of colorism, and racism throughout. Adeyemi says her aim was to teach via fantasy, in a non-preachy way:

“Oh man, I’m going to write a story that’s so good and so black that everyone’s going to have to read it even if you’re racist.”She's done it. If she can follow up the first with a similar second book, the franchise could be huge. Some spoilers ahead.

Zelie is a realist about her world, the parallel in our modern world is drivingwhileblack, movingwhileblack etc:

He wants to believe that playing by the monarchy’s rules will keep us safe, but nothing can protect us when those rules are rooted in hate.The difference is in this world Zelie gets an opportunity to put someone from the establishment, someone in a position of power no less, into her shoes by living her worst memories via his magic connector power. He almost instantly switches sides in the war, although things get more complicated towards the end.

There's some annoyances, I'm unsure whether to chalk this up to simplification to keep it YA approachable, but these rubbed me the wrong way:

- Major characters get paired up two by into into nice little symmetic relationships, which doesn't seem particularly plausible.

- Practicality of creating a temporary sea in a desert to sail some ships around in a fight to the death just seems laughable. I know the point was to demonstrate excess, but it's still a desert.

- Why didn't they use magic to just steal the artifact? Playing the ship deathmatch contest was just silly. But even worse, when they won what was supposed to be an unwinnable battle the contest owners just handed over the artifact. Why? It's very naive to think that would actually happen in the real world. These cutthroat blood-sport profiteers would just kill them and keep running the show.

- They almost died getting into a settlement of elite ninjas, but then the ninjas threw them a party, forgot to post guards, and the bad guys waltzed in and killed everybody. You can't be elite ninjas one day and dumb tacticians the next.

- The torture scenes seem way over the top for YA.

But it's a great YA read, I couldn't put it down.

4.5 stars

Tuesday, August 7, 2018

Jesus' Son by Denis Johnson (3.5 stars)

This book is very special, but at the same time I couldn't have read much more of it. Lucky it's very short.

It's a clever look inside the head of an addict, but without a focus or even much of a mention of the drugs, merely what reality looks like through that lens. Things don't make sense, events seem to unfold somewhat at random, and most of the choices of the narrator don't seem particularly logical.

The skill of the writing seems almost wasted on something which is just never going to make any sense, but occasionally there's a dark poetic sentence dropped that reminds you why you are reading this weird thing at all:

But nothing I could think up, no matter how dramatic or completely horrible, ever made her repent or love me the way she had at first, before she really knew me.

All day long he watched television from his bed. It wasn’t his physical condition that kept him here, but his sadness.

I'd recommend this, I don't think it's enjoyable, but it's pretty unique.

3.5 stars

Sunday, August 5, 2018

Escape from Spiderhead by George Saunders (5 stars)

An amazing short story. What would society by like if we could make a perfect designer drug for almost every purpose? Drugs for truth, drugs for love, drugs for torture. And how would we test their effects on humans? Saunders says his main objective is to provide a wild ride:

5 stars.

I tend to foster drama via bleakness. If I want the reader to feel sympathy for a character, I cleave the character in half, on his birthday. And then it starts raining. And he’s made of sugar.And boy does he deliver. This short story is fascinating, intense, and brutal with its characters. Reading George's thoughts about they story is also interesting, he didn't intend it to be commentary about pharma testing or treatment of death row prisoners. This was the core:

It might not be the case that one character is purely good, but rather that good is lurking in that person, and the story is about whether the good gets to emerge. And likewise the evil: it sits inside a person, sort of latent, waiting for the right combination of circumstances.

5 stars.

Winter in the Blood by James Welch (4 stars)

This is a powerful novel, but it is hard to like. Welch is Native American and writes a bleak story of a Native American man stumbling through life, clashing culturally as he moves between the nearby white town and his rural life on a farm. The writing reminded me of Cormac McCarthy:

I struggled with rating this book, but I'm giving it 4 stars because I still remember the lost feeling it gave me.

4 stars

On it were written the name, John First Raise, and a pair of dates between which he had managed to stay alive.He has a series of surreal, dreamlike conversations in various seedy bars, and gets mixed up in multiple criminal dealings and fights for no obvious reason apart from feeling detached from life and alien inside this community.

Again I felt that helplessness of being in a world of stalking white men. But those Indians down at Gable's were no bargain either. I was a stranger to both and both had beaten me.The narration is distant, so I never really felt like I knew the main (unnamed) character, I was mostly just left with a sense of a life with many permanent holes that were far from being filled by a series of sexual encounters with lonely women.

I struggled with rating this book, but I'm giving it 4 stars because I still remember the lost feeling it gave me.

4 stars

Sunday, July 22, 2018

Accelerando by Charles Stross (3.5 stars)

This is a novel about post-singularity existence and post humanism, written by a computer scientist. It really shows. Apparently the initial inspiration came to Stross while working as a programmer during the dot com era, which is no more apparent than in this quote:

Bizarrely there's some action that livens things up right towards the end, but it turns out to be just a kid inside a VR environment with no morality boundaries, and is over swiftly.

I would love someone to take this new imagined reality, and make me believe it, give me a real 3 dimensional character, show me some real relationships and let me live them.

3.5 stars

He’s the guy who patented using genetic algorithms to patent everything they can permutate from an initial description of a problem domain—not just a better mousetrap, but the set of all possible better mousetraps. Roughly a third of his inventions are legal, a third are illegal, and the remainder are legal but will become illegal as soon as the legislatosaurus wakes up, smells the coffee, and panics.

and in this dig at religion that could only have come from a computer scientist:

Human consciousness is vulnerable to certain types of transmissible memetic virus, and religions that promise life beyond death are a particularly pernicious example because they exploit our natural aversion to halting states.

It feels nothing like the previous two books in the series, you can read it stand-alone. Some spoilers ahead.

Stross packs the novel with ideas, and there's an irreverence and whimsical cynicism that feels a little Douglas Adams at times. Like the AI based on uploaded brain scans of California spiny lobsters broadcast into space, later becoming the avatar for first contact inside an alien router with a race that essentially lurks near the router trying to scam new civilisations. 419 scams and pyramid schemes are alive and well post-singularity.

There's the matrioshka brain: a solar powered super computer that eventually grows to encase the sun to tap its energy for computation. And what I thought was a very novel solution to the Fermi paradox:

“I think we have the outline of the answer to the Fermi paradox. Transcendents don’t go traveling because they can’t get enough bandwidth—trying to migrate through one of these wormholes would be like trying to download your mind into a fruit fly,

Conscious civilizations sooner or later convert all their available mass into computronium, powered by solar output. They don’t go interstellar because they want to stay near the core where the bandwidth is high and latency is low, and sooner or later competition for resources hatches a new level of metacompetition that obsoletes them.”This is all very interesting stuff. Except the delivery is lacking. It's *lots* of exposition, very light characters, and generally missing a first person feel to anything. Lots of dense text like this makes for pretty boring reading, even if the ideas are interesting:

Not just our own neural wetware, mapped out to the subcellular level and executed in an emulation environment on a honking great big computer, like this: That’s not posthuman, that’s a travesty. I’m talking about beings who are fundamentally better consciousness engines than us merely human types, augmented or otherwise. They’re not just better at cooperation—witness Economics 2.0 for a classic demonstration of that—but better at simulation. A posthuman can build an internal model of a human-level intelligence that is, well, as cognitively strong as the original. You or I may think we know what makes other people tick, but we’re quite often wrong, whereas real posthumans can actually simulate us, inner states and all, and get it right. And this is especially true of a posthuman that’s been given full access to our memory prostheses for a period of years, back before we realized they were going to transcend on us.There's a political drama towards the end of the novel that is presented in the most boring way possible, essentially just people sitting around in a room talking about what is happening. No emotional connection to the story.

Bizarrely there's some action that livens things up right towards the end, but it turns out to be just a kid inside a VR environment with no morality boundaries, and is over swiftly.

I would love someone to take this new imagined reality, and make me believe it, give me a real 3 dimensional character, show me some real relationships and let me live them.

3.5 stars

Sunday, June 10, 2018

Iron Sunrise by Charles Stross (3.5 stars)

I enjoyed this book, but it didn't leave me with much to remember. Rachel's terrorist negotiation was something straight out of an action movie. Wednesday was a badass, and I was constantly wondering what was actually being done to her by the bad guys, and what was being done by her 'friend' Herman to weaponize her for the Eschaton's purposes.

Honestly it's been too long and I don't have much to say.

3.5 stars.

Honestly it's been too long and I don't have much to say.

3.5 stars.

Saturday, May 19, 2018

Singularity Sky by Charles Stross (3 stars)

This book was just good enough to continue to the next book. There's a lot of setup to essentially deliver a space opera version of "information wants to be free":

3 stars

Then along comes the Festival, which treats censorship as a malfunction and routes communications around it. The Festival won’t take no for an answer because it doesn’t have an opinion on anything; it just is.”According to Wikipedia Stross was looking for something to symbolize a society being invaded by something they completely didn't understand. He ended up using Edinburgh during the Edinburgh Fringe Festival for inspiration - hence "The Festival" and mimes featuring prominently...

The Mimes moved slowly, frequently fighting an invisible wind or trying to feel their way around intangible buildings, but they were remorseless. Mimes never slept, or blinked, or stopped moving.I liked the cornucopia machines, and Rachel's escape from the court martial was particularly entertaining. Also I liked the creativity in the original singularity: that humanity was somewhat randomly just transported all over the galaxy through wormholes such that the most distant settlements were sent many centuries into the past, and thus advanced well beyond Earth's technology level.

3 stars

Monday, April 23, 2018

Railsea: A Novel by China Meiville (2.5 stars)

I'm a huge Meiville fan, but I've been putting off reading this one because it sounded boring. It was.

Take Moby Dick, turn the ocean into dirt, ships into trains, whales into giant moles. That's pretty much it. The Railsea was ridiculous, but I was willing to look past that for a good story. It feels like Meiville has dialed down his usual dark and dirty world-building to make this YA, and I think that's what I missed the most.

I didn't care about any of the characters. The world building was light and unconvincing compared to New Crobuzon. Some people found all the replacing 'and' with ampersands infuriating, I didn't really care, but it was a silly gimmick. While it's third-person the narrator often addresses the reader, which makes it feel a bit more campfire-tale, and often addresses exactly what I was thinking, which was mostly:

2.5 stars

Take Moby Dick, turn the ocean into dirt, ships into trains, whales into giant moles. That's pretty much it. The Railsea was ridiculous, but I was willing to look past that for a good story. It feels like Meiville has dialed down his usual dark and dirty world-building to make this YA, and I think that's what I missed the most.

I didn't care about any of the characters. The world building was light and unconvincing compared to New Crobuzon. Some people found all the replacing 'and' with ampersands infuriating, I didn't really care, but it was a silly gimmick. While it's third-person the narrator often addresses the reader, which makes it feel a bit more campfire-tale, and often addresses exactly what I was thinking, which was mostly:

TIME FOR THE SHROAKES? Not yet.I guess some English teacher will enjoy assigning this to compare and contrast with Moby Dick, but it has nothing on the rest of his books.

2.5 stars

Sunday, April 1, 2018

1Q84 by Haruki Murakami (2 stars)

I had no idea what I was getting myself into here, well that's not entirely true, I had some vague trepidation about it being very literary and a bit slow. If I'd seen the length of the physical book I may never have picked it up, so I guess I have the kindle to thank there. Some spoilers ahead.

So I hopped on board. Murakami is obviously a gifted writer, and I had no trouble getting interested in the story. Something is amiss with the world after The Taxi, and I start speculating about what Fuka-Eri is: alien? robot?

It seemed like just adding Tengo as a co-author would have been a whole lot simpler, but whatever, I'll allow it. Why does Tengo never say his girlfriend's name, does she even exist? What's up with Aomame and head shapes for random sexual partners? I go and listen to Janáček’s Sinfonietta.

Then HOLY CRAP there's little people crawling out of someone's mouth, but the story just continues on as before. OK that was nuts, now I'm really hooked what's going to happen?

Every now and then there's a literary gem dropped, I loved the suspense built by this single line:

At page 545 I wrote "Good god, is anything ever going to happen in this book?" and I lost heart.

By the time I'm living through Aomame spending a few months looking at a playgound in what feels like real time when she has a perfectly good private investigator that could find Tengo with a few phonecalls I just wanted it to end. There's only so much time I can spend inside someone's head staring at a slide in a playground. Just make it stop.

Random new characters of no importance are introduced at page 1000. I couldn't care less.

2 stars.

So I hopped on board. Murakami is obviously a gifted writer, and I had no trouble getting interested in the story. Something is amiss with the world after The Taxi, and I start speculating about what Fuka-Eri is: alien? robot?

It seemed like just adding Tengo as a co-author would have been a whole lot simpler, but whatever, I'll allow it. Why does Tengo never say his girlfriend's name, does she even exist? What's up with Aomame and head shapes for random sexual partners? I go and listen to Janáček’s Sinfonietta.

Then HOLY CRAP there's little people crawling out of someone's mouth, but the story just continues on as before. OK that was nuts, now I'm really hooked what's going to happen?

Every now and then there's a literary gem dropped, I loved the suspense built by this single line:

“According to Chekhov,” Tamaru said, rising from his chair, “once a gun appears in a story, it has to be fired.”At about page 500 the Tengo and Aomame threads are linked for the first time! Ah-hah!

At page 545 I wrote "Good god, is anything ever going to happen in this book?" and I lost heart.

“Tell me,” he said, “how much of Air Chrysalis is real? How much of it really happened?” “What does ‘real’ mean,” Fuka-Eri asked without a question mark.Some more people get killed which is renews my interest, but I have no idea who is a real person or a doha anymore. And I don't really care.

“Ho ho,” said the keeper of the beat.OK that's creepy and cool, do more of that. Please scare me, at least it will keep me interested.

By the time I'm living through Aomame spending a few months looking at a playgound in what feels like real time when she has a perfectly good private investigator that could find Tengo with a few phonecalls I just wanted it to end. There's only so much time I can spend inside someone's head staring at a slide in a playground. Just make it stop.

Random new characters of no importance are introduced at page 1000. I couldn't care less.

“It’s so detailed and beautifully written, and I feel like I can grasp the structure of that lonely little planet. But I can’t seem to go forward. It’s like I’m in a boat, paddling upstream. I row for a while, but then when I take a rest and am thinking about something, I find myself back where I started.Yep, where are we going here? Will this ever end?

“Ho, ho,” one of the Little People intoned from somewhere.So here it is, a vast dreamscape with some occasional weird moments but really mostly just a lot of sitting around and reflecting, rehashing a single hand-holding incident over and over, and describing lots of intricate boring detail, for 1,300 pages. Murakami is a great writer, but the only possible way I could of enjoyed this was if it was at least 600 pages shorter and some of the weird shit actually went somewhere.

2 stars.

Sunday, February 11, 2018

Artemis: A Novel by Andy Weir (1 star)

Andy Weir can write a mean engineer, I mean, like a 5 star engineer that keeps me reading all night. Imagine my surprise to be giving his next book one star.

I thought Weir really knew engineers, but it turns out he really knows male engineers, he has no idea how to write a female character. As a male, I probably also have no idea, but I'm 100% certain that the internal monologue of his female protagonist Jazz was much more like a horny male teenager than a woman. At one point "boobs" are mentioned 5 times in 10 pages. There's an over-the-top focus on her sex life, including a whole side plot about a re-usable condom, which seems imagined direct from the brain of a 18 year old boy.

1 star.

I thought Weir really knew engineers, but it turns out he really knows male engineers, he has no idea how to write a female character. As a male, I probably also have no idea, but I'm 100% certain that the internal monologue of his female protagonist Jazz was much more like a horny male teenager than a woman. At one point "boobs" are mentioned 5 times in 10 pages. There's an over-the-top focus on her sex life, including a whole side plot about a re-usable condom, which seems imagined direct from the brain of a 18 year old boy.

They only come about once a week. The next one wouldn’t be for three days. Thank God. There’s nothing more annoying than trust-fund boys looking for “moon poon.”Apart from the cringeworthy gender caricature there's the dumb heist, which is implausible on many levels (spoilers):

- Business model for optic fiber that apparently has to be manufactured on the moon. There's no way this is profitable.

- Jazz being a genius at pretty much everything, but basically is a lowlife smuggler wasting her time on a implausible act of sabotage for which the motivations also seem ridiculous

- Not being punished when it's found out she was a saboteur/terrorist

- The whole climax - both the getting into that situation and getting out of it with few deaths

And you have to read dialogue like this:

“He’s right, Dad. I am an asshole. But Artemis needs an asshole right now and I got drafted.”Could he save it with the technology? That was amazing in the Martian. No. It's space welding all the way down, nothing else. The brief for this book was "make a space welding textbook sexy so 18 year olds will want to read it".

1 star.

Thursday, January 25, 2018

The Stone Sky by N.K Jemisin (3.5 stars)

What's more impressive than winning the Hugo twice in a row? How about three consecutive years for the same book series? It's been too long since I read this so reviewing is hard, but from my notes:

Nassun is supposed to be what, 10 years old? She is written like a 40 year old, which dropped me out of suspending disbelief a few times.

If it's so easy for Hoa to travel underground, why isn't he just transporting the whole comm instead of having them die on the journey?

This miles-long staircase down into the earth is all very dramatic, but there is no society with automatic lights and doors capable of surviving an apocalypse that wouldn't use a vehicle of some kind to travel those distances, which doesn't work on a staircase. Not to mention building a staircase that big would be a giant PITA.

My favorite quote:

Overall I felt the pace was slower than necessary, and I enjoyed it less than the first two, but it was a decent conclusion to the series.

3.5 stars

Nassun is supposed to be what, 10 years old? She is written like a 40 year old, which dropped me out of suspending disbelief a few times.

If it's so easy for Hoa to travel underground, why isn't he just transporting the whole comm instead of having them die on the journey?

This miles-long staircase down into the earth is all very dramatic, but there is no society with automatic lights and doors capable of surviving an apocalypse that wouldn't use a vehicle of some kind to travel those distances, which doesn't work on a staircase. Not to mention building a staircase that big would be a giant PITA.

My favorite quote:

“I think,” Hoa says slowly, “that if you love someone, you don’t get to choose how they love you back.”

Overall I felt the pace was slower than necessary, and I enjoyed it less than the first two, but it was a decent conclusion to the series.

3.5 stars

Tuesday, January 2, 2018

The Obelisk Gate by N.K Jemisin (4 stars)

What's more amazing than winning the Hugo? Also winning the Hugo for the sequel. It's a great read.

There's plenty of minor things that annoyed me, like (spoilers) how Jija gave up his whole way of life to save Nassun, but then continues to consider killing her. I just didn't buy that he would be that deeply anti-orogene he'd be willing to kill yet another of his own children. Make your bed and lie in it.

But at the same time, it was incredibly powerful showing how part of Nassun's childhood was killed because she had to learn how to manipulate her father:

The weird second-person narration continues, acknowledged by the author:

There also seemed to be a lot of weaknesses and contradictions in how Nassun chooses to exercise her power in the battle for Castrima-over:

Very entertaining series.

4 stars

There's plenty of minor things that annoyed me, like (spoilers) how Jija gave up his whole way of life to save Nassun, but then continues to consider killing her. I just didn't buy that he would be that deeply anti-orogene he'd be willing to kill yet another of his own children. Make your bed and lie in it.

But at the same time, it was incredibly powerful showing how part of Nassun's childhood was killed because she had to learn how to manipulate her father:

I also didn't buy Essun marrying this guy. She obviously knew he was incredibly anti-orogene and she and her children would be in incredible danger. Why him? Was she so desperate that was the best she could do? There wasn't any mention of that, or explanation for how they came together.It is a manipulation. Something of her is warped out of true by this moment, and from now on all her acts of affection toward her father will be calculated, performative. Her childhood dies, for all intents and purposes. But that is better than all of her dying, she knows.

The weird second-person narration continues, acknowledged by the author:

And not only that but it will occasionally switch between third-person and second-person, which has to be explained in the text.I WANT TO KEEP TELLING THIS as I have: in your mind, in your voice, telling you what to think and know. Do you find this rude? It is, I admit. Selfish. When I speak as just myself, it’s difficult to feel like part of you. It is lonelier. Please; let me continue a bit longer.

There also seemed to be a lot of weaknesses and contradictions in how Nassun chooses to exercise her power in the battle for Castrima-over:

So just ice the doorway where they have to come in? It makes no sense. I did like those crazy bugs though.“That army fills both Castrima-over and the forest basin,” you say. “You’ll pass out before you can ice half of a circle that big.”

Very entertaining series.

4 stars

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)